One term for an author stepping outside and addressing the reader is called "anti-illusionism." It does not have to be speaking directly to reader, but any device really, that takes the reader / viewer, out of the story illusion.

John Fowles made it fashionable with French Lieutenant’s Woman. At the same time, many filmmakers began to play with it (the film of the book does not do the device justice). Especially avant-garde / art filmmakers. I was a young filmaker and student at the time, and impressionable, and it was a big influence on me.

Fowles actually played more deeply with the idea in that he incorporated the device into his narrator’s voice, thus, really ADDING a new layer of illusionism embedded in the supposed anti-illusionism!

Chapter 13 begins: "I do not know," and the narrator proceeds to discuss the difficulty of writing a story when characters behave independently rather than do his bidding. Charles, he complains, did not return to Lyme as the narrator had intended but willfully went down to the Dairy to ask about Sarah. But, the narrator concedes, times have changed, and the traditional novel is out of fashion, according to some. Novels may seem more real if the characters do not behave like marionettes and narrators do not behave like God. So the narrator, in effect, promises to give his characters the free will that people would want a deity to grant them. Likewise, the narrator will candidly admit to the artifice of the narration and will thereby treat his readers as intelligent, independent beings who deserve more than the manipulative illusions of reality provided in a traditional novel. Source: http://www.fowlesbooks.com/novelsof.htm September 12, 2008.

It is quite controversial it seems. One of the points of employing anti-illusionism is to remind the viewer / reader that this is a work of art, something to contemplate, not just something to get caught up in. Something to analyze while reading/viewing, not just something to lose oneself in.

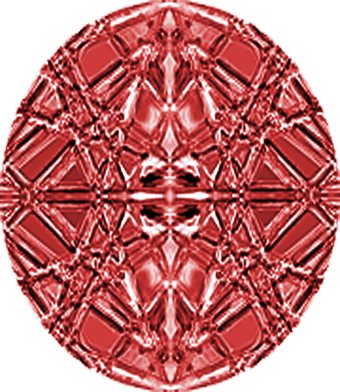

I began employing the device in my art as soon as I began painting digitally. An example here. A portrait of a beautiful young woman (Ice Tea) – but see how I made the foreground clearly manufactured, not real, surreal really. For that was one of my “issues” with being a visual artist. I hated that people just got lost in the portrait of a beautiful woman, or scene, or whatever, and did not actually reflect on or analyze art. By adding the “un-real” the anti-illusion, I was able to force them to really look at it as a work of art, not just something beautiful and shallow. In exhibits, some people loved this. They told me how they really looked at the brush strokes, wondered why she was in glass, thought about it after they were confronted with the strange ground. Others were offended.

I think the same holds true in use of the device in literature. Some people want only to be caught up in the story. Others enjoy being encouraged to look at it more objectively, to be reminded it is a story while reading because of the use of the device.

Mediabench™

Mediabench™

Home of interactive designer, developer, author, artist, producer Terry Bailey

Ice Tea

digital painting by Terry Bailey © 2004

Ice Tea

is a digital painting I created due to my fascination with paintings of glass by early Flemish and Dutch painters since my childhood,

growing up in San Francisco and visiting the de Young museum frequently to view them. The essay below explores another of my art

fascinations, anti-illusionism, and how it informs my art. The painting is printed in a Limited Edition of 50 as a gicleé on

watercolor paper and is 30.5 inches by 39" in size.

Exhibit History

Ice Tea was exhibited at Disney's Gallery at the Marloboro School in 2006 as part of a

3-person show on the digital arts. It was also my honor to spend a full day with the students there

after the exhibit opened, talking about my art and multimedia with the students, and seeing their new media projects.

Others of My Digital Paintings

Tess for Warhol and Gehry

also there

are images on the Gallery Page (button above) and more paintings with details posted soon as I rebuild my website.